Article Published by Paul N. Chugay, MD; Nikolas V. Chugay, DO

KEY POINTS

- Implant selection is paramount, making sure that the right implant is chosen to meet the patient’sneeds without exceeding the capacity of the leg based on preoperative measurements and the surgeon’sassessment of esthetics.

- Careful and judicious dissection is key to this procedure. Overdissection results in extra dead spacethat can result in seroma, hematoma, and possible implant malposition.

- Avoidance of injury to the short saphenous vein that runs in the midline posteriorly and lays deep tothe investing fascia of the leg along the surface of the gastrocnemius.

- Layered closure with absorbable sutures ensures a more esthetically pleasing scar postoperatively.

- Wrap for compression in the first 24 hours to minimize implant mobility and keep swelling compartmentalized.Postoperative use of compression stockings with a grading of 20 to 30 mm Hg helps tominimize the dead space and the risk of implant movement until scar tissue has developed.

Introduction

A well-sculpted calf is something often sought after by male patients presenting for cosmetic surgery. Despite hours in the gym doing calf raises, lunges, and squats, some men are not able to achieve the volume and definition desired in the calf region. Using semisolid silicone prostheses, a man with thin legs can achieve a more athletic masculine contour. Via a 5 cm incision in the popliteal fossa, implants can be placed to augment the medial head of the gastrocnemius, the lateral head of the gastrocnemius, or provide overall volume augmentation of the calf to produce a more bulky calf region. Regardless of the implants used, calf augmentation is a straightforward and reproducible procedure that provides excellent results in the vast majority of male patients presenting for improvement in perceived disproportion of the leg.

History Of The Procedure

Over the course of the last 40 years since the introduction of calf augmentation for reconstructive purposes, there have been various surgeons who have proposed novel implant shapes and sizes along with varying locations for the placement of the implants.1–12 The implant most commonly used today is largely based on the silicone gel implants of Glitzenstein. However, Carlsen was the first to use calf implants back in 1972.13 His initial implant was made out of silastic foam. Glitzenstein, in 1979, used calf implants for patients with atrophy of the leg and muscular aplasia. Unlike Carlsen, his implants were designed from silicone gel. In 1984, Szalay introduced torpedo-shaped implants that were placed beneath the fascia. In his technique, however, he did recommend the use of relaxing incisions in the fascia.4 Aiache in 1991 introduced lenticularshaped implants.12 In 2006, Gutstein described a new silicone prosthesis that enhances the curved medial lower leg, which he termed a “combined calf-tibial implant.”7 The early pioneers of the procedure, Carlsen and Glizenstein, introduced the implant into a subfascial plane. However, in 2003, Kalixto and Vergara6 described a calf augmentation with placement of the implant in a submuscular pocket, between the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. The dissection that they proposed was done far away from the union of the gastrocnemius muscles where there were no vessels or nerves that could be damaged. It was noted, however, that these patients had a more tedious dissection and prolonged recovery than the patients who had undergone subfascial implant placement as described in previous reports. Use of muscle relaxants was paramount in these patients. The rationale for submuscular placement, according to the authors, was that they were able to gain better camouflaging of the implant. In 2004, Nunes described a method for calf augmentation that placed the implant in a supraperiosteal plane associated with fasciotomies. Ultimately, it is at the surgeon’s discretion where to place the implant; however, based on anatomic studies, it seems that the subfascial plane is a safe plane that allows for reproducible results with minimal risk of postoperative complications and significantly less pain from the patient’s perspective.11 It is for this reason that the author favors a subfascial plane in the medial aspect of the calf for the vast majority of augmentations.

Relevant Anatomy

Fig. 1. Major muscles of the calf region: gastrocnemius and soleus. (From Chugay PN. Chapter 35: Calf Augmentation. In: Steinbrech, DS, ed. Male Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 1st ed. Thieme; 2020:420.)

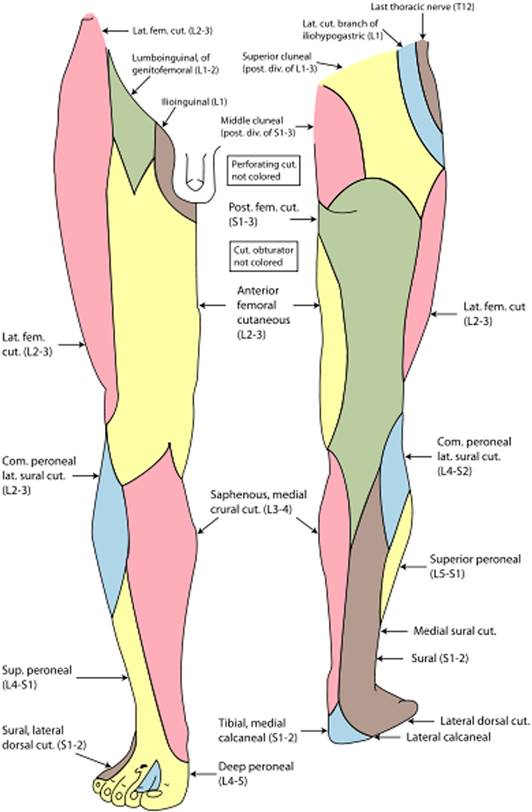

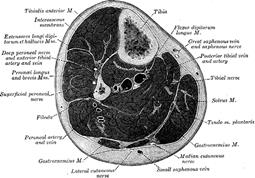

As a result of anatomic studies11 and operative dissections, the anatomy of the calf region is well understood. The calf is made up of 2 muscle groups: the gastrocnemius and the soleus (Fig. 1). The gastrocnemius has 2 heads and lies superficial to the deeper soleus muscle. The fibers of the 2 heads unite at an angle in the midline of the muscle in a tendinous raphe, which expands into a broad aponeurosis. The aponeurosis, gradually contracting, unites with the tendon of the soleus and forms the calcaneal tendon (Achilles tendon). In performing the dissection to attain a subfascial plane, the lateral and medial cutaneous nerves, branches of the peroneal nerve and tibial nerve, respectively, are potentially encountered. These nerves provide sensory innervation to the skin (Fig. 2). The medial sural cutaneous nerve originates from the tibial nerve of the sciatic and descends between the 2 heads of the gastrocnemius. It can be identified before diving between the heads of the gastrocnemius in the upper midline calf region. The lateral sural cutaneous nerve supplies the skin on the posterior and lateral surfaces of the leg and travels in a subcutaneous plane alongside the small (short) saphenous vein, joining with the medial sural cutaneous nerve to form the sural nerve. Major arterial, venous, and nerve structures are deep within the calf and remain undisturbed during a routine calf augmentation procedure (Fig. 3). The subfascial plane, both medially and laterally, is relatively avascular, allowing for the creation of a relatively bloodless plane. That being said, care must be taken to avoid injury to the short saphenous vein which lay deep to the investing fascia of the leg and superficial to the gastrocnemius in the midline posteriorly. This vein drains into the popliteal vein in the popliteal fossa. Care must be exercised when placing implants to produce a more “bulky” calf as this implant spans the midline and injury to the short saphenous vein is a risk.

Indications

Calf augmentation was originally designed to fill defects left following oncologic surgery, after trauma or infection, or due to genetic abnormalities that left patients with a “shrunken” lower leg. There are many causes for unilateral or bilateral calf deformities and they include but are not limited to the following: (1) congenital hypoplasia due to agenesis of a calf muscle or adipose tissue reduction; (2) as sequelae of clubfoot (talipes equinovarus), cerebral palsy, polio, and spina bifida; (3) due to poliomyelitis or osteomyelitis; and (4) following fractures of the femur and as a result of burn contractures.1,2,13,14 Since its initial introduction, calf augmentation surgery has become a widely popular esthetic procedure to help patients gain more shapely legs. Bodybuilders and some male sports enthusiasts may want to demonstrate a more bulky leg or what we like to term the “football calf.” Other men, presenting for surgery, may just want to have some increased volume in the medial and/or lateral calf to produce a more gentle curve and shapely leg. Ultimately, it is a simple disproportion between the thigh and calf that brings patients in for surgery. Using silicone implants, one can bring about greater harmony to the male leg and produce a more muscular and “masculine” leg.

Fig. 2. The lateral and medial cutaneous nerves dermatomes are seen here. These are branches of the peroneal nerve and tibial nerve, respectively, and are potentially encountered in dissection for calf augmentation. These nerves provide sensory innervation to the skin in the area. (Adapted from Gray H. Anatomy of the Human Body. https://www.bartleby.com/107/indexillus.html.)

The Consultation/Implant Selection

Fig. 3. Major neurovascular structures are seen in this cross-section of the midportion of the calf. When performing a subfascial augmentation (as is our standard), these structures are relatively safe from injury as most major structures are deep to the muscle of the calf. (Adapted from Gray H. Anatomy of the Human Body. https://www.bartleby.com/107/indexillus. html.)

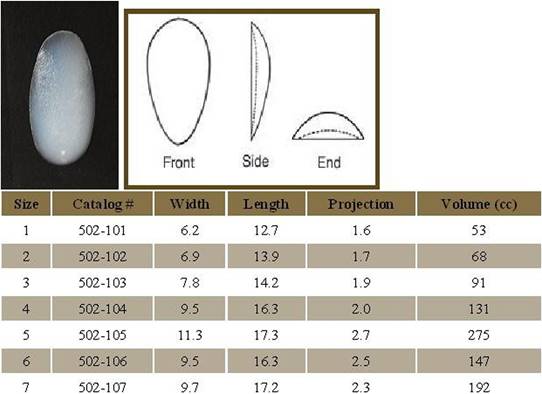

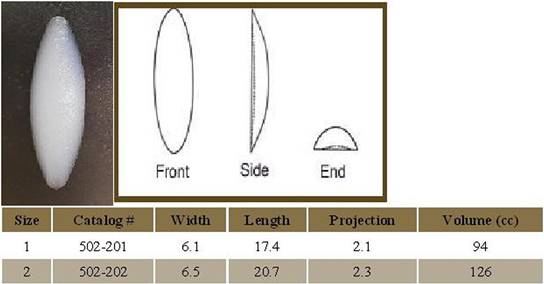

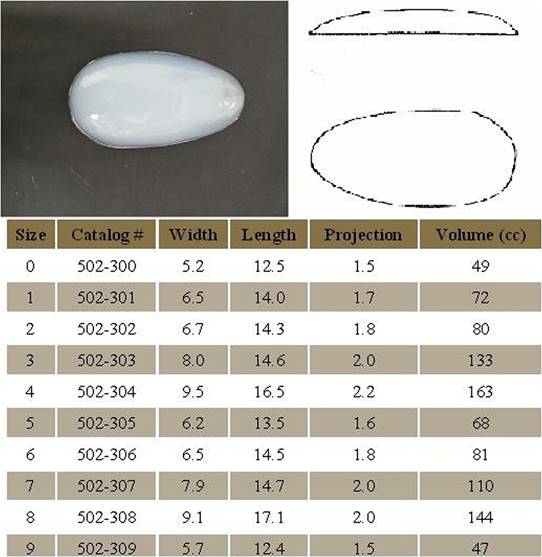

The consultation begins with a thorough medical history of the patient. Special attention is taken to ask specifically about trauma to the extremity, history of surgery to the foot or ankle, history of vascular insufficiency which may put blood flow at risk, history of venous insufficiency or leg swelling which may prolong postoperative edema in the lower extremity, and any history of nerve damage or sensory deficits as may be seen in patients with diabetes mellitus. At the time of consultation, the patient is asked what specifically about their calf bothers them. Patients with unrealistic goals are deemed poor candidates for calf augmentation. Patients who have congenital anomalies, a significant size disparity between the 2 calves, or bilateral hypoplasia are informed that several surgeries may be required to attain symmetry and achieve the augmentation they desire. In the typical consultation, patients are asked if their deficiency lies primarily in the medial aspect of the calf, the lateral aspect of the calf, or whether they would like a larger calf size overall. The reason for this distinction is to help the surgeon select the right implant style for the surgery. After completion of the history, the patient’s calves are evaluated. First, symmetry of the 2 sides is assessed and any disparity is brought to the attention of the patient. Although most patients present with a pre-existing asymmetry of the calves, not many patients note the difference and this can be a source of medicolegal matters in the future. The physician then evaluates the quality of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle. A person who has very thin tissues or significant hypoplasia of the calf may not be able to adequately accommodate a large implant. Next, the patient’s calves are measured in circumference at the midportion of the calf. A second measurement, from the popliteal fossa (proposed incision line) to the origin of the Achilles tendon, is also taken. Having this second measurement allows one to assess the maximum length of implant that can be accommodated in the calf. We favor AART calf implants (Fig. 4) as they provide sufficient augmentation of the region while still being pliable and supple, more like natural tissue. Each of the different style implants has a range of sizes to fit each patient’s need (http://aartinc.net/calf-implants/). Regardless of the implant chosen, the position of the implant is still in the subfascial plane and minimizes dissection around key neurovascular structures. With experience, the surgeon will be better able to determine the best implant for each patient. In reconstructive cases, the size of the defect is assessed and the affected leg is compared with the contralateral, unaffected leg. Using measurements as noted earlier and the surgeon’s personal experience, the surgeon should be able to determine the best implant to suit the patient’s needs. The goal in purely esthetic cases is to enlarge the calf volume. The key in both instances is to choose the implant that is right for the patient rather than succumbing to the patient’s demands. An implant that is too large may risk significant complications and may produce an unesthetic appearance.

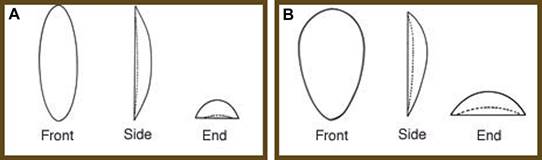

Available Implants Figs. 5–7.

Preoperative Planning And Marking

With the patient in the erect position, the proposed site of incision is marked, measuring approximately 5 cm. The site of incision should be in line with the patient’s natural crease in the popliteal fossa. The exact popliteal crease can be accentuated by asking the patient to stand upright and hold on to a stationary object while flexing one knee at a time. Once the site of the incision is marked, the site of the proposed implant is marked taking into account the patient’s anatomy and existing deficit along with the desires of the patient (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. (A–C) Preoperative markings for calf augmentation surgery. Note the site of the incision in the popliteal fossa and the outline of the site for calf augmentation. The markings for implant position are done in concert with the patient to maximize patient satisfaction postoperatively. Notice that the implants are placed in different positions in 5a and 5c, depending on the individual desires of the patient. NOTE: Anterior placement is limited by the investing fascia.

Operative Technique

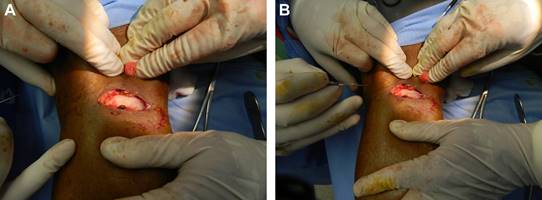

The surgery is typically performed under general anesthesia or sedation to minimize patient discomfort. Two grams of Ancef are administered before the incision for prophylaxis (if allergic to penicillin or cephalosporin, then clindamycin 300 mg IV is administered). The patient is repositioned in the prone position after administration of anesthesia. The calves are then prepped with chlorhexidine and each calf is injected with a total of 50 cc of 1% lidocaine with epinephrine in the area of proposed implant placement. The patient is then reprepped and draped in a sterile fashion. A 5 cm incision is made in the popliteal fossa in line with preoperative markings. Subsequently, dissection is performed through the subcutaneous tissues. Dissection is carried to the level of the popliteal fascia. On reaching the fascia, a 15-blade scalpel is used to make a transverse incision (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. (A) Dissection through the popliteal incision has been completed with blunt dissection and electrocautery to the level of the fascia. (B) With the fascia exposed, an incision in the fascia is made with a 15 blade producing a bulging of the subfascial fat. Metzenbaum scissors are used to widen the opening in the fascia.

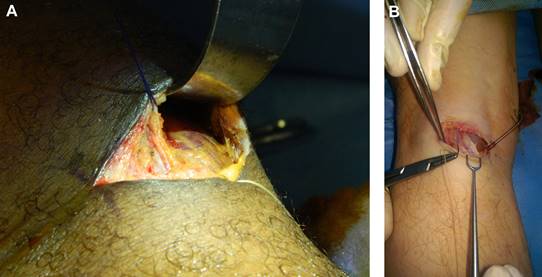

This is extended with Metzenbaum scissors medially and laterally. At this point, 2-0 Vicryl stay sutures are placed in each section of the fascia (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. The dissection of the gastrocnemius is complete. Stay sutures are placed into the cut edges of the fascia cephalically and caudally. The medial head of the gastrocnemius is fully exposed. The proposed site of implant is noted on the medial aspect of the leg (in red). NOTE: Notice the tissues laterally intact. Overaggressive dissection to the midline of the leg and laterally may damage the short saphenous vein.

While performing this dissection, care is taken to avoid injury to the short saphenous vein which runs in the midline posteriorly and lays deep to the investing fascia of the leg along the surface of the gastrocnemius (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. (A) Dissection of the subfascial plane is complete (looking caudally toward the foot). The stay sutures are in place with the medial head of the gastrocnemius visible. The pocket has been dissected medially showing ample space for placement of the implant. Tissue planes are maintained, which allows for closure at the end.

(B) Again, tissues in the midline of the calf are not violated for risk of damage to the short saphenous vein seen here depicted in the middle of the photo (bluish tinge at the point of the needle within the driver)— view is again looking caudally to the feet with the dissection for medial calf augmentation.

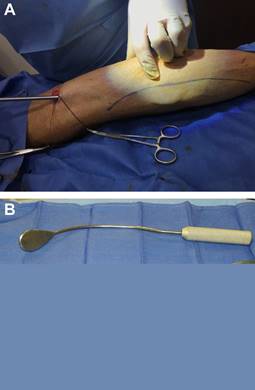

A subfascial plane, beginning beneath the popliteal fascia and extending into the deep investing fascia of the leg, is then dissected using blunt finger dissection and a spatula dissector, ensuring an adequate plane for the implant (in line with preoperative markings/patient wishes) (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. (A) Dissection of the subfascial pocket using a spatula dissector, taking care to stay within the borders of the outlined implant. (B) A common spatula dissector frequently used in breast augmentation surgery that is quite useful in calf augmentation procedures.

Once a sufficient pocket is dissected, the pocket is irrigated with a solution containing normal saline, betadine, Ancef, and gentamicin. 15 cc of 0.5% Marcaine is injected into the pocket for postoperative analgesia. An implant is then placed. Symmetry is assessed. At this point, closure is begun. The fascia is reapproximated with 2-0 Vicryl suture in an interrupted fashion (Fig. 13). The deep dermis is reapproximated with 3-0 Monocryl suture in a buried fashion.

Fig. 13. Closure of the deep investing fascia of the leg using 2-0 Vicryl suture. To facilitate closure and take tension off of the ends of the fascia, the knee is flexed by the assistant.

The skin is closed in a subcuticular fashion with 30 Monoderm Quill suture. The same procedure is mirrored on the contralateral side. An occlusive dressing is applied. The legs are wrapped with Coban, and the patient is then taken to the postanesthesia care unit (Figs. 14–16).

Fig. 14. Case 1: (A–D) A 42-year-old man is shown before and 1 week after bilateral calf augmentation with style 2, size 2 implants.

Fig. 15. Case 2: (A–D) A 51-year-old man shown before and 9 months after bilateral calf augmentation with style 2, size 2 implants.

Fig. 16. Case 3: (A–F) A 29-year-old man before and 1 year after bilateral calf augmentation with style 2, size 2 implants.

Postoperative Care/instructions

Postoperatively the patient may begin ambulating starting on the evening of the procedure. They may shower POD 2, making sure to keep dressings clean and dry. Patients are then allowed to begin light activity at week 2 and full unrestricted activity at weeks 4 to 6. Patients are asked to wear compression stockings with a grading of 20 to 30 mm Hg for 4 weeks postoperatively to prevent dead space, thereby helping to reduce the risk of seroma formation and allowing scar tissue to form around the implant in the desired position. The legs are to be elevated as much as possible to allow for better lymphatic/venous drainage.

Discussion

Although calf augmentation is a relatively straight-forward procedure, there are complications that the surgeon should be aware of and that should be fully discussed with the patient preoperatively (Box 1). Although the risk of infection is relatively low, ranging from 05 to 3.3%,1 it can largely be avoided with good sterile surgical technique. Species identified in the author’s experiences were isolated to Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus epidermidis, relatively common skin flora.

Seromas are statistically the most common complication occurring in calf augmentation surgery, occurring in approximately 6% of cases in most large volume studies.4,11,15,16 The treatment of choice remains percutaneous aspiration. This complication is best prevented with patient compliance with compression stockings and avoidance of vigorous activity in the early post operative period and proper implant placement at the time of surgery, thereby minimizing dead space.

Although a rare occurrence, because of the relatively avascular plane of dissection for the calf augmentation procedure, a hematoma is always possible if damage is done to the vessels that perforate the investing fascia of the leg.11

BOX 1

Potential complications of calf augmentation surgery

- Infection

- Seroma

- Hematoma

- Asymmetry

- Implant visibility

- Hypertrophic scarring

- Hyperpigmentation of the scar

- Wound dehiscence

- Capsular contracture

- Nerve injury (permanent or temporary; motoror sensory)

- Compartment syndrome

Data from Chugay PN. Chapter 35: Calf Augmentation. In: Steinbrech, DS, ed. Male Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 1st ed. Thieme; 2020. p. 419-434

In the event of a hematoma, rapid evacuation, pocket irrigation, and reimplantation are the mainstays of therapy. This complication is best prevented by meticulous hemostasis at the time of surgery and good compression of the calf postoperative to prevent potential space creation.

Patients complaining of asymmetry and implant visibility are 2 complications that can be avoided by good preoperative consultation and evaluation. The vast majority of patients have a pre-existing asymmetry. This needs to be fully shown and discussed with the patient to avoid problems postoperatively. To avoid creating asymmetry with respect to implant position, the markings of the proposed site of implant placement should be thoroughly discussed and confirmed with the patient preoperatively. In cases of pre-existing asymmetry, creating greater asymmetry can be minimized by using a static anatomic structure such as the malleolus as a reference point for the implant tracings. With respect to implant visibility, all patients need to be made aware of thinner tissues that may be covering the implant may be more prone to revealing the borders of the implant versus a patient that has more subcutaneous tissue that can camouflage the implants.

Owing to the significant mobility in the calf region, hyperpigmented scars and hypertrophic scars along with wound dehiscence are indeed risks. To minimize these complications, the surgeon should be meticulous in his or her closure of the wound. By closing in anatomic layers and minimizing tension at the skin level, these risks may be lessened. To help in closure of the fascia, the patient’s knee is flexed at the time of closure to ensure good purchase of the fascia with the suture. Lastly, patients are asked to avoid overzealous activity for the first 4 to 6 weeks to again minimize tension on the scar. Without question, the use of scar gels and sunscreens can help to avoid a noticeable postoperative scar.

One of the possible late complications of calf augmentation is capsular contracture. The literature in calf augmentation has described a rate between 0%3–5,10 and 5%.1 If a patient presents with signs/symptoms of capsular contracture (eg, induration of the implant site, tightness in the leg, newonset pain, new-onset swelling), ultrasound or CT evaluation of the affected extremity is warranted. If a thickened capsule is identified, typically characterized by calcifications, then a partial or complete capsulectomy is warranted. The reality is that removal of the capsule may be quite difficult in the confined space of the calf and may require larger, unsightly incisions in more severe cases.

Major motor or sensory nerve injury in calf augmentation procedures is rare as the majority of dissection is performed in areas devoid of major neurovascular structures. It is quite common for patients to complain of some numbness over the area of the popliteal fossa postoperatively; however, this returns within 1 to 3 months postoperatively. Major motor and sensory deficits, particularly in the first 24 to 72 hours after surgery, can accompany compartment syndrome and this must be ruled out immediately if any significant deficits are appreciated. Compartment syndromes, typically seen in trauma, involve an acute increase in pressure inside a closed space, thereby impairing blood flow to the affected space and potentially putting the limb at risk for loss. Clinical signs of compartment syndrome include the 6 P’s: pain, poikilothermia, pallor, paresthesias, paralysis, and pulselessness. In conscious patients, pain out of proportion to examination is the prominent symptom. Pain with passive range of motion is particularly troubling. In the lower extremity, numbness between the first and second toes due to compression of the deep peroneal nerve in the anterior compartment is the hallmark of early compartment syndrome. Progression to paralysis can occur, and loss of pulses is a late sign. By the time pulselessness has occurred, it may be too late for limb salvage. In patients with a compatible history and a tense extremity, a clinical diagnosis may be sufficient. If the diagnosis is in doubt, compartment pressures may be measured with a hand-held Stryker device. An absolute pressure greater than 30 mm Hg in any compartment, or a pressure within 30 mm Hg of the diastolic blood pressure in hypotensive patients, or a patient with a concerning history who demonstrates the constellation of signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome are all possible indications for surgical compartment release via fasciotomy17; or, in the case of calf augmentation, simply opening the wound and removing the offending agent. In the case of calf augmentation, the cause of compartment syndrome is typically due to placing too large an implant in too small a space, thereby increasing the compartment pressure and causing arterial insufficiency or venous outflow compromise. This has been seen in the author’s experience particularly in treating hypoplastic extremities, as seen in club foot deformity. Because the patient is postoperative, there is an implant in place and postoperative edema is present. Therefore, diagnosis may be problematic. In an affected compartment, accurate pressure readings may be difficult to obtain and may be inaccurate because of the patient’s postoperative state. Clinical assessment and clinical diagnosis is the mainstay in compartment syndrome in the postoperative calf patient. Patients who are suspected of having compartment syndrome should have serial neurovascular checks and any worsening of the patient’s examination warrants surgical intervention. A patient who is clinically stable has evidence of decreased pain or clinical improvement, and is cooperative may be a candidate for further close observation and neurovascular monitoring rather than immediate surgical intervention.18

Fig. 17. Case 4: (A–D) A 17-year-old man (BC) underwent unilateral calf augmentation for a hypoplastic left calf (style 2, size 1).

Although the vast majority of patients presenting for calf augmentation are seeking increased muscularity, treatment of the hypoplastic leg is something that bears discussion. In patients that have been afflicted with club foot, polio, or trauma, there is at times a noticeable discrepancy in the size of the lower extremities. For those patients wishing to achieve symmetry, a calf implant may be an ideal way to do so (Fig. 17). However, that being said, a single augmentation may be insufficient to achieve symmetry. Lloyd Carlsen, knowing this full well, designed a custom expander to slowly expand the calf region without having to subject the patient to multiple operations and risk possible issues of skin slough and excessively elevated compartment pressures.15,16 Although the idea of an expander makes sense, many patients are unwilling to go through a prolonged expansion period, as is commonly seen in breast patients postmastectomy reconstruction. It has been my standard practice to place a moderate-sized silicone prosthesis into position as per the technique described previously. Then 6 months later, after having stretched out the proposed implant pocket, a second procedure can be performed with either a larger standard implant or a custom-made implant. Regardless of the second operation performed, the patient is able to enjoy a fairly normal lifestyle free of return doctor visits for expansion and the possible discomfort associated with uncomfortable ports. Although this method does require close attention in the postoperative period on the part of the patient and physician, it has been the author’s experience that patients are much more content with the idea of this approach than the concept of slow expansion over time (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. Case 5: Staged procedures for calf augmentation. (A–I) A 30-year-old man (AM) was born with club foot deformity of the left leg. He presented for improved symmetry. He agreed to a staged procedure to bring about greater symmetry. First, he underwent augmentation of the medial calf with a style 2, size 2 implant. Subsequently, 8 months later, he underwent lateral calf augmentation with a style 3, size 1 implant. The next step will be either increasing the size of one of the implants or fat grafting to the lower leg, above the ankle.

Calf Augmentation Utilizing Fat Instead Of Implants

One cannot have a thorough discussion of calf augmentation without mentioning the concept of fat grafting to the calf. Over the course of the development of the calf augmentation procedure, some physicians have begun to explore the use of fat grafting to correct hypoplastic calves.19–21 The use of fat injection for augmentation was explored to eliminate some of the common complications associated with implants: implant palpability, lack of correction of the ankle region, implant displacement, and the possibility of capsular contracture. Erol’s study of 2007 looked at 77 patients treated over a 10-year period with autologous fat and tissue cocktail injections, consisting of mini-micro grafts of dermis, fascia, and fat. They noted a moderate improvement in 13% of patients and a good improvement in 87% of patients. 75 to 200 cc of fat or tissue cocktail was injected into each leg to achieve the results noted in their study. These injections were repeated 2 to 4 times at 3-month intervals as was deemed necessary by the investigating physician. Although some surgeons swear by fat grafting and the use of a “natural” means of augmentation, I have found that fat grafting, specifically to the calf, does not always produce reliably pleasing results. The largest complaint typically noted in the author’s fat grafting population is that the overall augmentation is not to their satisfaction or that the augmentation is asymmetric. These complaints are largely due to the variability in fat take and the potential for fat cell death. In the hands of many cosmetic surgeons, the average patient can expect a fat take of 50% to 70% without the use of stem cells.22–26 However, this is largely dependent on placement of the fat in a place that has a rich blood supply that can foster the growth of the fat cells. When grafting to the calf, the calf muscles are already largely hypoplastic and so there is a lack of a robust blood supply to support fat cell take, in our opinion. This being said, fat is a natural option for those seeking augmentation without implants. The surgeon must be careful to explain variable fat take and the possible need for further fat transfers to achieve symmetry or achieve more prominent augmentation.

Summary

Calf augmentation with silicone implants is a procedure that can nicely enhance the physique of the male cosmetic patient in a reliable fashion and has a short learning curve. Overall patient satisfaction is quite high and can provide added volume medially, laterally, or to the overall calf region depending on the needs/desires of the patient.

Calf Augmentation Utilizing Fat Instead Of Implants

One cannot have a thorough discussion of calf augmentation without mentioning the concept of fat grafting to the calf. Over the course of the development of the calf augmentation procedure, some physicians have begun to explore the use of fat grafting to correct hypoplastic calves.19–21 The use of fat injection for augmentation was explored to eliminate some of the common complications associated with implants: implant palpability, lack of correction of the ankle region, implant displacement, and the possibility of capsular contracture. Erol’s study of 2007 looked at 77 patients treated over a 10-year period with autologous fat and tissue cocktail injections, consisting of mini-micro grafts of dermis, fascia, and fat. They noted a moderate improvement in 13% of patients and a good improvement in 87% of patients. 75 to 200 cc of fat or tissue cocktail was injected into each leg to achieve the results noted in their study. These injections were repeated 2 to 4 times at 3-month intervals as was deemed necessary by the investigating physician. Although some surgeons swear by fat grafting and the use of a “natural” means of augmentation, I have found that fat grafting, specifically to the calf, does not always produce reliably pleasing results.

The largest complaint typically noted in the author’s fat grafting population is that the overall augmentation is not to their satisfaction or that the augmentation is asymmetric. These complaints are largely due to the variability in fat take and the potential for fat cell death. In the hands of many cosmetic surgeons, the average patient can expect a fat take of 50% to 70% without the use of stem cells.22–26 However, this is largely dependent on placement of the fat in a place that has a rich blood supply that can foster the growth of the fat cells. When grafting to the calf, the calf muscles are already largely hypoplastic and so there is a lack of a robust blood supply to support fat cell take, in our opinion. This being said, fat is a natural option for those seeking augmentation without implants. The surgeon must be careful to explain variable fat take and the possible need for further fat transfers to achieve symmetry or achieve more prominent augmentation.

Summary

Calf augmentation with silicone implants is a procedure that can nicely enhance the physique of the male cosmetic patient in a reliable fashion and has a short learning curve. Overall patient satisfaction is quite high and can provide added volume medially, laterally, or to the overall calf region depending on the needs/desires of the patient.

CLINICS CARE POINTS

- Ensuring realistic expectations for calfaugmentation patients is paramount to havinggood results and having happy patients.

- Choose the right implant for every patientbased on patient desires and establishedesthetic norms

- Careful and judicious dissection is the key toavoiding complications intraoperatively andpostoperatively.

- Layered closure with absorbable sutures ensuresa more esthetically pleasing scarpostoperatively.

- Compression, compression, compression wrap for compression in the first 24 hoursto minimize implant mobility and keepswelling compartmentalized is an early interventionthat is key to success. Postoperativeuse of compression stockings with a gradingof 20 to 30 mm Hg helps to minimize thedead space and the risk of implant movementuntil scar tissue has developed.

- Aiache AE. Calf implantation. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989;83:488.

- Dini M, Innocenti A, Lorenzetti P. Aesthetic calf augmentation with silicone implants. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2002;26:490.

- Howard PS. Calf augmentation and correction of contour deformities. Clin Plast Surg 1991;18: 601.

- Szalay LV. Twelve years’ experience of calf augmen- tation. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1995;19:473.

- Niechajev I. Calf augmentation and restoration. Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;116:295.

- Kalixto MA, Vergara R. Submuscular calf implants. Aesthet Plast. Surg. 2003;27:135.

- Gutstein RA. Augmentation of the lower leg: a new combined calf-tibial implant. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;117:817–26.

- Nunes GO, Garcia DP. Calf Augmentation with supraperiostic solid prosthesis associated with fasciotomies. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2004;28:17.

- Gray H. Anatomy of the human body. Philadelphia (PA): Lea & Febiger; 1918.

- Chugay P, Chugay N. Calf augmentation: a single institution review of over 200 cases. Am J Cosmet Surg 2013;30(2):64–71.

- De la Pena-Salcedo JA, Soto-Miranda MA, Lopez- Salguero JF. Calf Implants: a 25 year experience and an anatomical review. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2012;36:261–70.

- Aiache AE. Calf contour correction with implants. Clin Plast Surg 1991;18:857–62.

- Carlsen LN. Calf augmentation: a preliminary report. Ann Plast Surg 1979;2:508.

- Glitzenstein J. Correction of the amyotrophies of the limbs with silicone prosthesis inclusions. Rev Bras Cir 1979;69:117.

- Carlsen LN, Voice SD. Calf augmentation. In: Vistnes LM, editor. Boston: Little Brown: Procedures in plas- tic surgery: how they do it, chapter 15; 1991. p. 281–94.

- Carlsen LN. Calf augmentation. Operative Tech- niques in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 1996; 3(2):145–53.

- Cothren CC, Biffl WL, Moore EE. Chapter 7. Trauma. In: Brunicardi FC, Andersen DK, Billiar TR, et al, editors. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery, 9e. McGraw Hill; 2010.

- Walsh J, Page S. Chapter 10. Rhabdomyolysis and Compartment Syndrome in Military Trainees. In Re- cruit Medicine.

- Erol OO, Gu¨ rlek A, Agaoglu G, et al. Calf augmenta- tion with autologous tissue injection. Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;6:121.

- Veber M Jr, Mojallal A. Calf augmentation with autol- ogous tissue injection. Plast Reconst Surg 2010;125: 423–4.

- Hendy A. Calf and leg augmentation: autologous fat or silicone implant? J Plast Reconst Surg 2010; 34(2):123–6.

- Coleman SR. Long-term survival of fat transplants: controlled demonstrations. Aesthetic Plast Surg 1995;19:421.

- Coleman SR. Structureal fat grafts: the ideal filler? Clin Plast Surg 2001;28:111.

- Pereira LH, Nicaretta B, Sterodimas A. Bilateral calf augmentation for aesthetic purposes. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2012;36:295–302.

- Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Correa WE, et al. Tissue engineering in plastic surgery: an up to date review of the current literature. Ann Plast Surg 2009;62: 97–103.

- Sterodimas A, de Faria J, Nicaretta B, et al. Tissue engineering with adipose-derive stem cells: current and future applications. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010;63(11):1886–92.